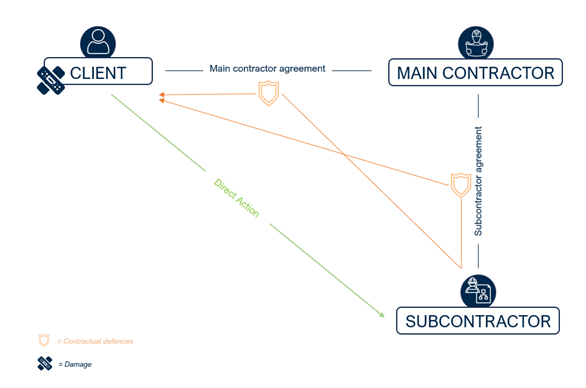

This is one of the biggest changes brought about by Book 6 for the real estate sector: from 1 January 2025, the principal will have the option of taking direct action against the subcontractor, which has been denied until now.

The repeal of the quasi-immunity of the auxiliary (formerly called the executive agent) prevented the principal from having such a means of action directly against the subcontractor or subcontractors. Conversely, based on article 1798 of the old Civil Code, subcontractors already have such a direct action against the principal.

At present, the principal generally has very few options for bringing an action against a subcontractor to whom the main contractor has entrusted all or part of its own work.

Unlike the subcontractor, who has a direct action against the principal under article 1798 of the old Civil Code, the principal can only bring an action forward against the subcontractor based on extra-contractual liability under two strict conditions:

-

Firstly, the subcontractor must not only be in breach of a contractual obligation but also in breach of a duty of care that would apply to everyone; and

-

This breach causes damage distinct from that caused by the contractual breach.

If these two conditions - which are rarely met in practice – are not met, the principal is prohibited from seeking to sue the executive agent (e.g. the subcontractor) extra-contractually.

At present, the principal is at a disadvantage in the event of bankruptcy of the main contractor, as the principal cannot act against the subcontractors of his defaulting co-contractor.

It should be noted, however, that in Book 5, which came into force on 1 January 2023, Article 5.110 now provides that a direct action may be granted by statute in very general terms. This provision opens the doors to other direct actions and discussions are already underway about direct actions as part of the drafting of the proposed legislation relating to Book 7 (“Special contracts”). At this stage, however, only direct actions by auxiliaries would be provided for (cf. art. 7.4.31 Civ. C.).

Book 6 takes a remarkable step forward in this respect in Article 6.3, which states that:

More specifically, a subcontractor's liability could, on this basis, be called into question directly by the principal.

As a mitigating measure, the legislator provides that the subcontractor (or, more generally, the auxiliary) will be able to rely on a double level of defences, firstly drawn from his own contract and, secondly, drawn from the main contract concluded between the principal and the main contractor.